- Hatred, Curfews, and a Man Who Smelled of Cows

- Where Beauty Knows No Borders

- Reading & Watching

- What we mistake for leadership

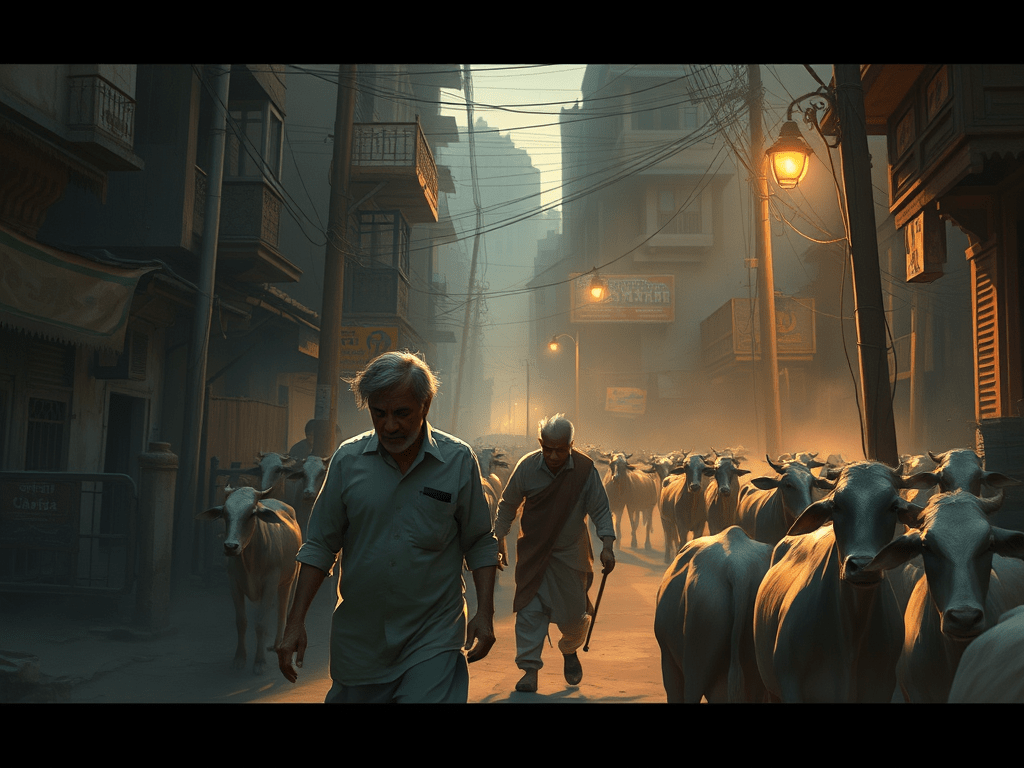

Hatred, Curfews, and a Man Who Smelled of Cows

Is it really that hard to love? Or, to put it more honestly, is it just far too easy to hate? I can dislike many things—traffic, small talk, badly written signs—but hatred is something else entirely. It is dislike that has put on combat boots and decided to go looking for trouble.

I grew up in Baroda (Gujarat, India) in the 1980s, a period best described as educationally committed but socially volatile. Riots were frequent, curfews longer, and logic largely optional. Our home sat firmly inside a curfew zone; my primary school, inconveniently, did not. School, it seemed, was non-negotiable—even when the city was periodically on fire.

So my father—Baba—improvised. He bribed auto-rickshaw drivers, and almost certainly a policeman or two, to smuggle me across barricaded streets so I wouldn’t miss maths lessons. Religious extremism was allowed a free run; missing school was not.

Around this time my maternal grandfather came to stay with us. He was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s and had developed a fondness for walking out of the house without the faintest idea of how to return. Most days my mother intercepted him with the precision of airport security. One day, however, life intervened.

Dadu went out in the afternoon. The sun went down. Dadu did not come back.

By the time my father returned from work, the house was thick with panic. Without hesitation—or perhaps without fully processing the wisdom of this decision—he went back out into a city already sliding into riot mode, to look for a man who no longer recognised addresses, landmarks, or indeed urgency.

After knocking on doors and interrogating strangers, Baba finally found Dadu sitting happily in the cowshed of our local milkman, in excellent spirits and questionable company of the buffaloes and the cows. The milkman explained that he assumed someone would eventually come looking and saw no reason to rush matters.

What emerged later was the more remarkable part of the story. While my father was there, a group of neighbours—Muslims, like the milkman—arrived and demanded that my father be handed over to them. The milkman refused. He explained, patiently, that this man was not a zealot, not a provocateur, not worth anyone’s outrage. He was simply retrieving his lost father-in-law.

My father came home with Dadu, the story, and a problem: Dadu smelled strongly of cows and their assorted outputs. This was resolved swiftly with a hose.

I revisit this memory often—not because I believe in religious madness (I don’t), but because I believe, somewhat unfashionably, that most people are decent when given half a chance. That even in situations perfectly engineered for violence, someone might choose restraint instead.

And whenever hatred feels tempting—efficient, righteous, justified—I think of consequences. Not in abstract terms, but practical ones. Who gets hurt. Who gets saved. And who ends up needing to be hosed down at the end of the evening.

Where Beauty Knows No Borders

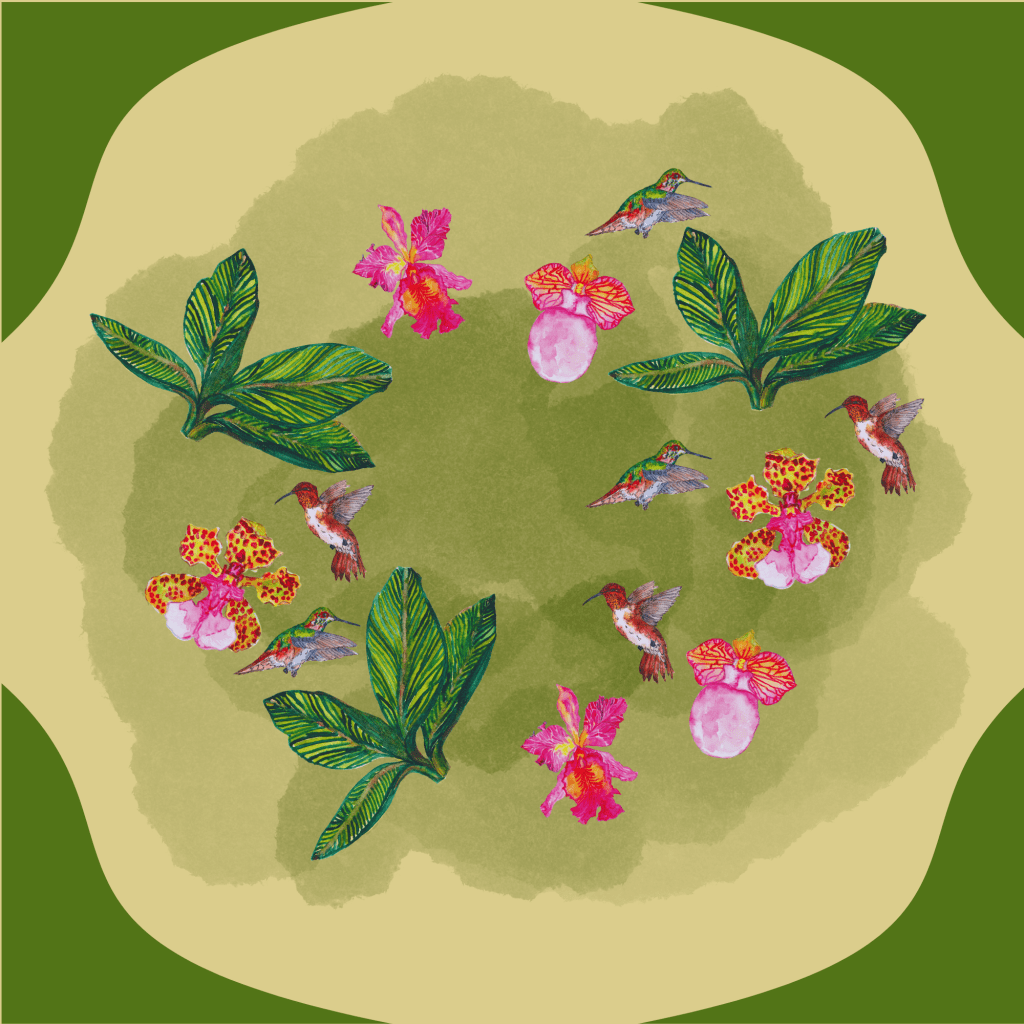

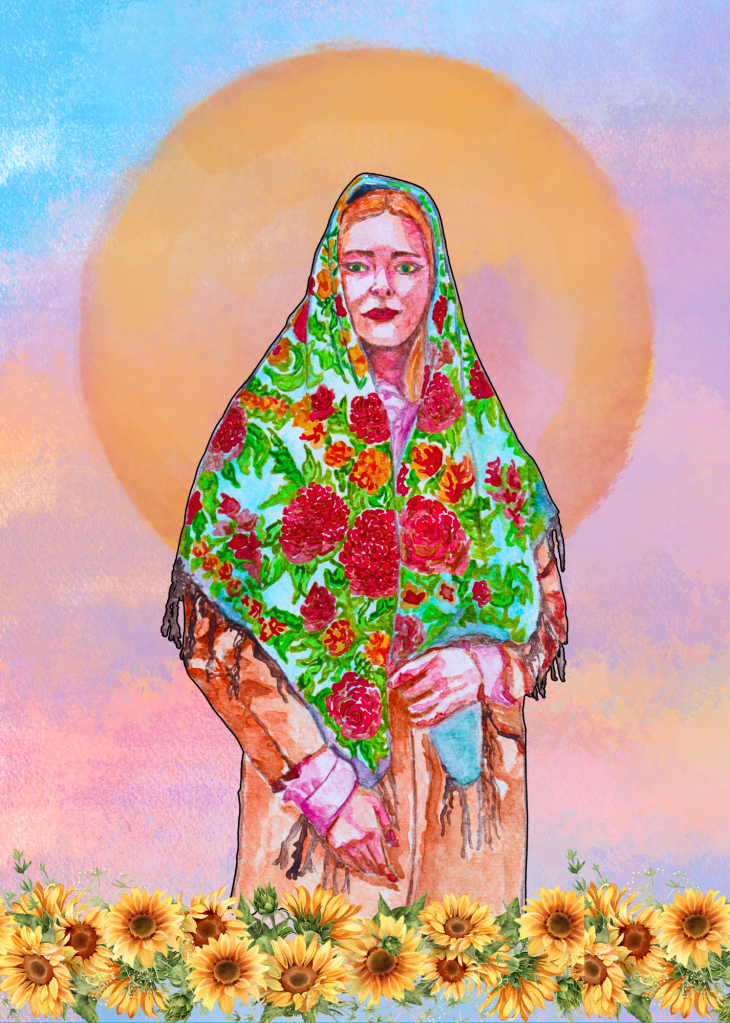

These pieces were painted slowly, by hand, using Sennelier watercolours — guided by colour, texture, and instinct. Flowers, birds, and faces come together as quiet symbols of resilience, softness, and continuity.

The portrait of the Ukrainian woman features a traditional floral headscarf (khustka), long worn as a symbol of identity, strength, and belonging. Set against sunflowers, it honours both cultural heritage and quiet defiance.

Across every piece, the message remains the same: beauty is universal — it transcends borders, languages, and circumstance.

Reading & Watching

★★★★★ The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny — Kiran Desai

A humane, emotionally intelligent novel about love, inheritance, and immigration. Desai captures the exhaustion of endless reinvention with poetry and restraint, building a world that feels deeply lived-in and quietly devastating.

★★★★★ Hamnet

Chloé Zhao’s restrained direction turns grief into something domestic and intimate. Jessie Buckley is extraordinary, Paul Mescal quietly devastating. A film that trusts silence, stillness, and emotional precision.

What we mistake for leadership

Perhaps forgetting harm, accountability, and the lessons of recent history was never the answer. What we need is a braver way of remembering—one that holds people to account without cruelty, speaks with conviction without contempt, and creates distance without dehumanising.

True leadership is not loud or divisive. It is courageous, steady, and humane.

Leaders are peace-makers, economists of consequence, stabilisers in chaos, facilitators, enablers, and problem-solvers. They do not fracture societies, reduce entire races or cultures to caricatures, or thrive on fear and hatred.

And yet, we keep mistaking noise for strength and division for direction.

If magic existed, I wouldn’t ask for erasure.

Just enough rain to clear our sight.

Leave a comment